Hearing loss can affect a child’s ability to develop communication, language, and social skills. The earlier children with hearing loss start getting services, the more likely they are to reach their full potential. If you are a parent and you suspect your child has hearing loss, trust your instincts and speak with your child’s doctor. Don’t wait!

I.What is Hearing Loss in Children?

Hearing Loss in Children

Hearing loss can affect a child’s ability to develop speech, language, and social skills. The earlier children with hearing loss start getting services, the more likely they are to reach their full potential. If you think that a child might have hearing loss, ask the child’s doctor for a hearing screening as soon as possible. Don’t wait!

What is Hearing Loss?

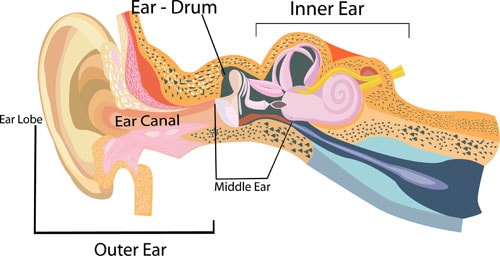

A hearing loss can happen when any part of the ear is not working in the usual way. This includes the outer ear, middle ear, inner ear, hearing (acoustic) nerve, and auditory system.

Signs and Symptoms

The signs and symptoms of hearing loss are different for each child. If you think that your child might have hearing loss, ask the child’s doctor for a hearing screening as soon as possible. Don’t wait!

Even if a child has passed a hearing screening before, it is important to look out for the following signs.

Signs in Babies

- Does not startle at loud noises.

- Does not turn to the source of a sound after 6 months of age.

- Does not say single words, such as “dada” or “mama” by 1 year of age.

- Turns head when he or she sees you but not if you only call out his or her name. This sometimes is mistaken for not paying attention or just ignoring, but could be the result of a partial or complete hearing loss.

- Seems to hear some sounds but not others.

Signs in Children

- Speech is delayed.

- Speech is not clear.

- Does not follow directions. This sometimes is mistaken for not paying attention or just ignoring, but could be the result of a partial or complete hearing loss.

- Often says, “Huh?”

- Turns the TV volume up too high.

Babies and children should reach milestones in how they play, learn, communicate and act. A delay in any of these milestones could be a sign of hearing loss or other developmental problem. Visit our web page to see milestones that children should reach from 2 months to 5 years of age.

II. Screening and Diagnosis

Hearing screening can tell if a child might have hearing loss. Hearing screening is easy and is not painful. In fact, babies are often asleep while being screened. It takes a very short time — usually only a few minutes.

Babies

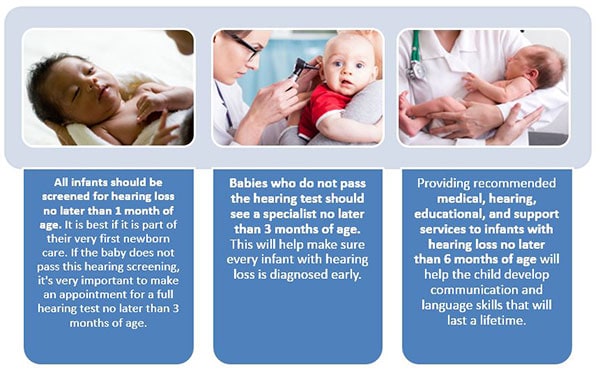

All babies should have a hearing screening no later than 1 month of age. Most babies have their hearing screened while still in the hospital. If a baby does not pass a hearing screening, it’s very important to get a full hearing test as soon as possible, but no later than 3 months of age.

Children

Children should have their hearing tested before they enter school or any time there is a concern about the child’s hearing. Children who do not pass the hearing screening need to get a full hearing test as soon as possible.

Treatments and Intervention Services

No single treatment or intervention is the answer for every person or family. Good treatment plans will include close monitoring, follow-ups and any changes needed along the way. There are many different types of communication options for children with hearing loss and for their families. Some of these options include:

- Learning other ways to communicate, such as sign language

- Technology to help with communication, such as hearing aids and cochlear implants

- Medicine and surgery to correct some types of hearing loss

- Family support services

Causes and Risk Factors

Hearing loss can happen any time during life – from before birth to adulthood.

Following are some of the things that can increase the chance that a child will have hearing loss:

- A genetic cause: About 1 out of 2 cases of hearing loss in babies is due to genetic causes. Some babies with a genetic cause for their hearing loss might have family members who also have a hearing loss. About 1 out of 3 babies with genetic hearing loss have a “syndrome.” This means they have other conditions in addition to the hearing loss, such as Down syndrome or Usher syndrome. Learn more about the genetics of hearing loss »

- 1 out of 4 cases of hearing loss in babies is due to maternal infections during pregnancy, complications after birth, and head trauma. For example, the child:

- Was exposed to infection, such as , before birth

- Spent 5 days or more in a hospital neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) or had complications while in the NICU

- Needed a special procedure like a blood transfusion to treat bad jaundice

- Has head, face or ears shaped or formed in a different way than usual

- Has a condition like a neurological disorder that may be associated with hearing loss

- Had an infection around the brain and spinal cord called meningitis

- Received a bad injury to the head that required a hospital stay

- For about 1 out of 4 babies born with hearing loss, the cause is unknown.

Prevention

Following are tips for parents to help prevent hearing loss in their children:

- Have a healthy pregnancy.

- Make sure your child gets all the regular childhood vaccines.

- Keep your child away from high noise levels, such as from very loud toys. Visit the National Institutes of Health’s websiteexternal icon to learn more about preventing noise-induced hearing loss.

Get Help!

- If you think that your child might have hearing loss, ask the child’s doctor for a hearing screening as soon as possible. Don’t wait!

- If your child does not pass a hearing screening, ask the child’s doctor for a full hearing test as soon as possible.

- If your child has hearing loss, talk to the child’s doctor about treatment and intervention services.

Hearing loss can affect a child’s ability to develop speech, language, and social skills. The earlier children with hearing loss start getting services, the more likely they are to reach their full potential. If you are a parent and you suspect your child has hearing loss, trust your instincts and speak with your child’s doctor.

Preventing Noise-Induced Hearing Loss

Hearing plays an essential role in communication, speech and language development, and learning. Even a small amount of hearing loss can have profound, negative effects on speech, language comprehension, communication, classroom learning, and social development. Studies indicate that without proper intervention, children with mild to moderate hearing loss, on average, do not perform as well in school as children with no hearing loss. This gap in academic achievement widens as students progress through school.1,2

An estimated 12.5% of children and adolescents aged 6–19 years (approximately 5.2 million) and 17% of adults aged 20–69 years (approximately 26 million) have suffered permanent damage to their hearing from excessive exposure to noise.3,4

Hearing loss can result from damage to structures and/or nerve fibers in the inner ear that respond to sound. This type of hearing loss, termed “noise-induced hearing loss,” is usually caused by exposure to excessively loud sounds and cannot be medically or surgically corrected. Noise-induced hearing loss can result from a one-time exposure to a very loud sound, blast, or impulse, or from listening to loud sounds over an extended period.

Hearing loss caused by exposure to loud sound is preventable.5 To reduce their risk of noise-induced hearing loss, adults and children can do the following:

- Understand that noise-induced hearing loss can lead to communication difficulties, learning difficulties, pain or ringing in the ears (tinnitus), distorted or muffled hearing, and an inability to hear some environmental sounds and warning signals

- Identify sources of loud sounds (such as gas-powered lawnmowers, snowmobiles, power tools, gunfire, or music) that can contribute to hearing loss and try to reduce exposure

- Adopt behaviors to protect their hearing:

- Avoid or limit exposure to excessively loud sounds

- Turn down the volume of music systems

- Move away from the source of loud sounds when possible

- Use hearing protection devices when it is not feasible to avoid exposure to loud sounds or reduce them to a safe level5

- Seek hearing evaluation by a licensed audiologist or other qualified professional, especially if there is concern about potential hearing loss

Learn more: Loud Noise Can Cause Hearing Loss

Genetics of Hearing Loss

Hearing loss has many causes. 50% to 60% of hearing loss in babies is due to genetic causes. There are also a number of things in the environment that can cause hearing loss. 25% or more of hearing loss in babies is due to “environmental” causes such as maternal infections during pregnancy and complications after birth. Sometimes both genes and environment work together to cause hearing loss. For example, there are some medicines that can cause hearing loss, but only in people who have certain mutations in their genes.

Genes contain the instructions that tell the cells of people’s bodies how to grow and work. For example, the instructions in genes control what color a person’s eyes will be. There are many genes that are involved in hearing. Sometimes, a gene does not form in the expected manner. This is called a mutation. Some mutations run in families and others do not. If more than one person in a family has hearing loss, it is said to be “familial”. That is, it runs in the family.

About 70% of all mutations causing hearing loss are non-syndromic. This means that the person does not have any other symptoms. About 30% of the mutations causing hearing loss are syndromic. This means that the person has other symptoms besides hearing loss. For example, some people with hearing loss are also blind.

The cochlea (the part of the ear that changes sounds in the air into nerve signals to the brain) is a very complex and specialized part of the body that needs many instructions to guide its development and function. These instructions come from genes. Changes in any one of these genes can result in hearing loss. The GJB2 gene is one of the genes that contains the instructions for a protein called connexin 26; this protein plays an important role in the functioning of the cochlea. In some populations about 40% of newborns with a genetic hearing loss who do not have a syndrome, have a mutation in the GJB2 gene.

Screening and Diagnosis of Hearing Loss

Hearing Screening

Hearing screening is a test to tell if people might have hearing loss. Hearing screening is easy and not painful. In fact, babies are often asleep while being screened. It takes a very short time — usually only a few minutes.

CDC Report: Infants with Congenital Disorders Identified Through Newborn Screening — United States, 2015–2017

Babies

- All babies should be screened for hearing loss no later than 1 month of age. It is best if they are screened before leaving the hospital after birth.

- If a baby does not pass a hearing screening, it’s very important to get a full hearing test as soon as possible, but no later than 3 months of age.

Older Babies and Children

- If you think a child might have hearing loss, ask the doctor for a hearing test as soon as possible.

- Children who are at risk for acquired, progressive, or delayed-onset hearing loss should have at least one hearing test by 2 to 2 1/2 years of age. Hearing loss that gets worse over time is known as acquired or progressive hearing loss. Hearing loss that develops after the baby is born is called delayed-onset hearing loss. Find out if a child may be at risk for hearing loss.

- If a child does not pass a hearing screening, it’s very important to get a full hearing test as soon as possible.

Full Hearing Test

All children who do not pass a hearing screening should have a full hearing test. This test is also called an audiology evaluation. An audiologist, who is an expert trained to test hearing, will do the full hearing test. In addition, the audiologist will also ask questions about birth history, ear infection and hearing loss in the family.

There are many kinds of tests an audiologist can do to find out if a person has a hearing loss, how much of a hearing loss there is, and what type it is. The hearing tests are easy and not painful.

Some of the tests the audiologist might use include:

Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) Test or Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (BAER) Test

Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) or Brainstem Auditory Evoked Response (BAER) is a test that checks the brain’s response to sound. Because this test does not rely on a person’s response behavior, the person being tested can be sound asleep during the test.

ABR focuses only on the function of the inner ear, the acoustic (hearing) nerve, and part of the brain pathways that are associated with hearing. For this test, electrodes are placed on the person’s head (similar to electrodes placed around the heart when an electrocardiogram (EKG) is done), and brain wave activity in response to sound is recorded.

Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE)

Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE) is a test that checks the inner ear response to sound. Because this test does not rely on a person’s response behavior, the person being tested can be sound asleep during the test.

Behavioral Audiometry Evaluation

Behavioral Audiometry Evaluation will test how a person responds to sound overall. Behavioral Audiometry Evaluation tests the function of all parts of the ear. The person being tested must be awake and actively respond to sounds heard during the test.

Infants and toddlers are observed for changes in their behavior such as sucking a pacifier, quieting, or searching for the sound. They are rewarded for the correct response by getting to watch an animated toy (this is called visual reinforcement audiometry). Sometimes older children are given a more play-like activity (this is called conditioned play audiometry).

With the parents’ permission, the audiologist will share the results with the child’s primary care doctor and other experts, such as:

- An ear, nose and throat doctor, also called an otolaryngologist

- An eye doctor, also called an ophthalmologist

- A professional trained in genetics, also called a clinical geneticist or a genetics counselor

For more information about hearing tests, visit the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association websiteexternal icon.

Get Help!

- If a parent or anyone else who knows a child well thinks the child might have hearing loss, ask the doctor for a hearing screening as soon as possible. Don’t wait!

- If the child does not pass a hearing screening, ask the doctor for a full hearing test.

- If the child is diagnosed with a hearing loss, talk to the doctor or audiologist about treatment and intervention services.

Hearing loss can affect a child’s ability to develop communication, language, and social skills. The earlier children with hearing loss start getting services, the more likely they are to reach their full potential. If you are a parent and you suspect your child has hearing loss, trust your instincts and speak with your doctor.

III. Types of Hearing Loss

A hearing loss can happen when any part of the ear or auditory (hearing) system is not working in the usual way.

Outer Ear

The outer ear is made up of:

- the part we see on the sides of our heads, known as pinna

- the ear canal

- the eardrum, sometimes called the tympanic membrane, which separates the outer and middle ear

Middle Ear

The middle ear is made up of:

- the eardrum

- three small bones called ossicles that send the movement of the eardrum to the inner ear

Inner Ear

The inner ear is made up of:

- the snail shaped organ for hearing known as the cochlea

- the semicircular canals that help with balance

- the nerves that go to the brain

Auditory (ear) Nerve

This nerve sends sound information from the ear to the brain.

Auditory (Hearing) System

The auditory pathway processes sound information as it travels from the ear to the brain so that our brain pathways are part of our hearing.

There are four types of hearing loss:

- Conductive Hearing Loss

Hearing loss caused by something that stops sounds from getting through the outer or middle ear. This type of hearing loss can often be treated with medicine or surgery.

- Sensorineural Hearing Loss

Hearing loss that occurs when there is a problem in the way the inner ear or hearing nerve works.

- Mixed Hearing Loss

Hearing loss that includes both a conductive and a sensorineural hearing loss.

- Auditory Neuropathy Spectrum Disorder

Hearing loss that occurs when sound enters the ear normally, but because of damage to the inner ear or the hearing nerve, sound isn’t organized in a way that the brain can understand. For more information, visit the National Institute of Deafness and Other Communication Disordersexternal icon.

The degree of hearing loss can range from mild to profound:

- Mild Hearing Loss

A person with a mild hearing loss may hear some speech sounds but soft sounds are hard to hear.

- Moderate Hearing Loss

A person with a moderate hearing loss may hear almost no speech when another person is talking at a normal level.

- Severe Hearing Loss

A person with severe hearing loss will hear no speech when a person is talking at a normal level and only some loud sounds.

- Profound Hearing Loss

A person with a profound hearing loss will not hear any speech and only very loud sounds.

Hearing loss can also be described as:

- Unilateral or Bilateral

Hearing loss is in one ear (unilateral) or both ears (bilateral).

- Pre-lingual or Post-lingual

Hearing loss happened before a person learned to talk (pre-lingual) or after a person learned to talk (post-lingual)

- Symmetrical or Asymmetrical

Hearing loss is the same in both ears (symmetrical) or is different in each ear (asymmetrical).

- Progressive or Sudden

Hearing loss worsens over time (progressive) or happens quickly (sudden).

- Fluctuating or Stable

Hearing loss gets either better or worse over time (fluctuating) or stays the same over time (stable). - Congenital or Acquired/Delayed Onset

Hearing loss is present at birth (congenital) or appears sometime later in life (acquired or delayed onset).

IV. Hearing Loss Treatment and Intervention Services

No single treatment or intervention is the answer for every child or family. Good intervention plans will include close monitoring, follow-ups and any changes needed along the way. There are many different options for children with hearing loss and their families.

Some of the treatment and intervention options include:

- Working with a professional (or team) who can help a child and family learn to communicate.

- Getting a hearing device, such as a hearing aid.

- Joining support groups.

- Taking advantage of other resources available to children with a hearing loss and their families.

Early Intervention and Special Education

Early Intervention (0-3 years)

Hearing loss can affect a child’s ability to develop speech, language, and social skills. The earlier a child who is deaf or hard-of-hearing starts getting services, the more likely the child’s speech, language, and social skills will reach their full potential.

Early intervention program services help young children with hearing loss learn language skills and other important skills. Research shows that early intervention services can greatly improve a child’s development.

Babies that are diagnosed with hearing loss should begin to get intervention services as soon as possible, but no later than 6 months of age.

There are many services available through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act 2004 (IDEA 2004).external icon Services for children from birth through 36 months of age are called Early Intervention or Part C services. Even if your child has not been diagnosed with a hearing loss, he or she may be eligible for early intervention treatment services. The IDEA 2004 says that children under the age of 3 years (36 months) who are at risk of having developmental delays may be eligible for services. These services are provided through an early intervention system in your state. Through this system, you can ask for an evaluation.

Special Education (3-22 years)

Special education is instruction specifically designed to address the educational and related developmental needs of older children with disabilities, or those who are experiencing developmental delays. Services for these children are provided through the public school system. These services are available through the Individuals with Disabilities Education Improvement Act 2004 (IDEA 2004), Part B.

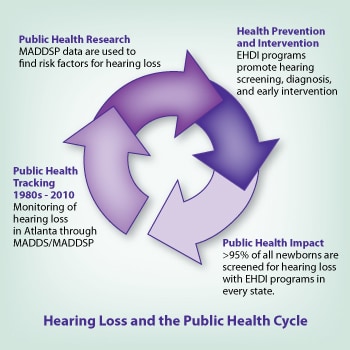

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Program

Every state has an Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program. EHDI works to identify infants and children with hearing loss. EHDI also promotes timely follow-up testing and services or interventions for any family whose child has a hearing loss. If your child has a hearing loss or if you have any concerns about your child’s hearing, call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO or contact your local EHDI Program coordinatorexternal icon to find available services in your state.

Technology

Many people who are deaf or hard-of-hearing have some hearing. The amount of hearing a deaf or hard-of-hearing person has is called “residual hearing”. Technology does not “cure” hearing loss, but may help a child with hearing loss to make the most of their residual hearing. For those parents who choose to have their child use technology, there are many options, including:

- Hearing aids

- Cochlear or brainstem implants

- Bone-anchored hearing aids

- Other assistive devices

Hearing Aids

Hearing aids make sounds louder. They can be worn by people of any age, including infants. Babies with hearing loss may understand sounds better using hearing aids. This may give them the chance to learn speech skills at a young age.

There are many styles of hearing aids. They can help many types of hearing losses. A young child is usually fitted with behind-the-ear style hearing aids because they are better suited to growing ears.

Cochlear and Auditory Brainstem Implants

A cochlear implant may help many children with severe to profound hearing loss — even very young children. It gives that child a way to hear when a hearing aid is not enough. Unlike a hearing aid, cochlear implants do not make sounds louder. A cochlear implant sends sound signals directly to the hearing nerve.

Persons with severe to profound hearing loss due to an absent or very small hearing nerve or severely abnormal inner ear (cochlea), may not benefit from a hearing aid or cochlear implant. Instead an auditory brainstem implant may provide some hearing. An auditory brainstem implant directly stimulates the hearing pathways in the brainstem, bypassing the inner ear and hearing nerve.

Both cochlear and brainstem implants have two main parts — the parts that are placed inside the inner ear, the cochlea, or base of the brain, the brainstem ear during surgery, and the parts that are worn outside the ear after surgery. The parts outside the ear send sounds to the parts inside the ear.

Bone-Anchored Hearing Aids

This type of hearing aid can be considered when a child has either a conductive, mixed or unilateral hearing loss and is specifically suitable for children who cannot otherwise wear ‘in the ear’ or ‘behind the ear’ hearing aids.

Other Assistive Devices

Besides hearing aids, there are other devices that help people with hearing loss. Following are some examples of other assistive devices:

- FM System

An FM system is a kind of device that helps people with hearing loss hear in background noise. FM stands for frequency modulation. It is the same type of signal used for radios. FM systems send sound from a microphone used by someone speaking to a person wearing the receiver. This system is sometimes used with hearing aids. An extra piece is attached to the hearing aid that works with the FM system.

- Captioning

Many television programs, videos, and DVDs are captioned. Television sets made after 1993 are made to show the captioning. You don’t have to buy anything special. Captions show the conversation spoken in soundtrack of a program on the bottom of the television screen.

- Other devices

There are many other devices available for children with hearing loss. Some of these include:

- Text messaging

- Telephone amplifiers

- Flashing and vibrating alarms

- Audio loop systems

- Infrared listening devices

- Portable sound amplifiers

- TTY (Text Telephone or teletypewriter)

Medical and Surgical

Medications or surgery may also help make the most of a person’s hearing. This is especially true for a conductive hearing loss, or one that involves a part of the outer or middle ear that is not working in the usual way.

One type of conductive hearing loss can be caused by a chronic ear infection. A chronic ear infection is a build-up of fluid behind the eardrum in the middle ear space. Most ear infections are managed with medication or careful monitoring. Infections that don’t go away with medication can be treated with a simple surgery that involves putting a tiny tube into the eardrum to drain the fluid out.

Another type of conductive hearing loss is caused by either the outer and or middle ear not forming correctly while the baby was growing in the mother’s womb. Both the outer and middle ear need to work together in order for sound to be sent correctly to the inner ear. If any of these parts did not form correctly, there might be a hearing loss in that ear. This problem may be improved and perhaps even corrected with surgery. An ear, nose, and throat doctor (otolaryngologist) is the health care professional who usually takes care of this problem.

Placing a cochlear implant, auditory brainstem implant, or bone-anchored hearing aid will also require a surgery.

Learning Language

Without extra help, children with hearing loss have problems learning language. These children can then be at risk for other delays. Families who have children with hearing loss often need to change their communication habits or learn special skills (such as sign language) to help their children learn language. These skills can be used together with hearing aids, cochlear or auditory brainstem implants, and other devices that help children hear.

Family Support Services

For many parents, their child’s hearing loss is unexpected. Parents sometimes need time and support to adapt to the child’s hearing loss.

Parents of children with recently identified hearing loss can seek different kinds of support. Support is anything that helps a family and may include advice, information, having the chance to get to know other parents that have a child with hearing loss, locating a deaf mentor, finding childcare or transportation, giving parents time for personal relaxation or just a supportive listener.

V.How People with Hearing Loss Learn Language

People with hearing loss and their families often need special skills to be able to learn language and communicate. These skills can be used together with hearing aids, cochlear implants, and other devices that help people hear. There are several approaches that can help, each emphasizing different language learning skills.

Some families choose a single approach because that’s what works best for them. Other people choose skills from two or more approaches because that’s what works best for them.

Following are language approaches, and the skills that are sometimes included in each of them:

- Auditory-Oral

Natural Gestures, Listening, Speech (Lip) Reading, Spoken Speech - Auditory-Verbal

Listening, Spoken Speech - Bilingual

American Sign Language and English - Cued Speech

Cueing, Speech (Lip) Reading - Total Communication

Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE), Signing Exact English (SEE), Finger Spelling, Listening, Manually Coded English (MCE), Natural Gestures, Speech (Lip) Reading, Spoken Speech

Communication Tools

American Sign Language

American Sign Language (ASL) is a language itself. While English and Spanish are spoken languages, ASL is a visual language.

ASL is a complete language. People communicate using hand shapes, direction and motion of the hands, body language, and facial expressions. ASL has its own grammar, word order, and sentence structure. People can share feelings, jokes, and complete ideas using ASL.

Like any other language, ASL must be learned. People can take ASL classes and start teaching their baby even while they are still learning it. A baby can learn ASL as a first language. Also, experts in ASL can work with families to help them learn ASL.

Children can use many other skills with ASL. Finger spelling is one skill that is almost always used with ASL. Finger spelling is used to spell out words that don’t have a sign — such as names of people and places.

Manually Coded English (MCE)

Manually Coded English (MCE) is made up of signs that are a visual code for spoken English. MCE is a code for a language — the English language. Many of the signs (hand shapes and hand motions) in MCE are borrowed from American Sign Language (ASL). But unlike ASL, the grammar, word order, and sentence structure of MCE are similar to the English language.

Children and adults can use many other communication tools along with MCE. One that is commonly used is finger spelling, which is used to spell out words that don’t have a sign in MCE — such as names of people and places.

Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE)

Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE) (sometimes called Pidgin Signed English (PSE)) has developed between people who use American Sign Language (ASL), and people who use Manually Coded English (MCE), using signs based on ASL and MCE. This helps them understand each other better. CASE is flexible, and can be changed depending on the people using it.

Other communication tools can be used with CASE. Often, finger spelling is used in combination with CASE. Finger spelling is used to spell out words that don’t have a sign, such as names of people and places.

Cued Speech

Cued Speech helps people who are deaf or hard-of-hearing better understand spoken languages.

When watching a person’s mouth, many speech sounds look the same on the face even though the sounds heard are not the same. For instance, the words “mat,” “bat,” and “pat,” look the same on the face even though they sound very different. When “cueing” English, the person communicating uses eight hand shapes and four places near the mouth to help the person looking tell the difference between speech sounds. Cued Speech allows the person to make out sounds and words when they are using other building blocks, such as speech reading (lip reading) or auditory training (listening).

Finger Spelling

With Finger Spelling the person uses hands and fingers to spell out words. Hand shapes represent the letters in the alphabet. Finger Spelling is used with many other communication methods; it is almost never used by itself. It is most often used with American Sign Language (ASL), Conceptually Accurate Signed English (CASE), and Manually Coded English (MCE) to spell out words that don’t have a sign, such as the names of places or people.

Natural Gestures

“Natural Gestures” — or body language — are actions that people normally do to help others understand a message. For example, if a parent wants to ask a toddler if he or she wants to be picked up, the parent might stretch out her arms and ask, “Up?” For an older child, the parent might motion with her arms as she calls the child to come inside. Or, the parent might put a first finger over her mouth and nose to show that the child needs to be quiet.

Babies will begin to use this building block naturally if they can see what others are doing. This building block is not taught, it just comes naturally. It is always used with other building blocks.

Listening / Auditory Training

Most people who are deaf or hard-of-hearing have some hearing. This is called “residual hearing.” Some people rely or learn how to maximize their residual hearing (auditory training). This building block is often used in combination with other building blocks (such as hearing aids, cochlear implants, and other assistive devices).

Listening might seem easy to a person with hearing. But for a person with hearing loss, Listening is often hard without proper training. Like all other tools, the skill of Listening must be learned. Often a speech-language pathologist (a professional trained to teach people how to use speech and language) will work with the person with hearing loss and the family.

Spoken Speech

People can use speech to express themselves. Speech is a skill that many people take for granted. Learning to speak is a skill that can help build language.

Speech or learning to speak is often used in combination with hearing aids, cochlear implants, and other assistive devices that help people maximize their residual hearing. A person with some residual hearing may find it easier to learn speech than a person with no residual hearing. Since speech can only be used by a person to express him or herself other building blocks, such as hearing with a hearing aid, must be added in order to help the person understands what is being said so they can communicate with others.

Speaking may seem easy to a person with hearing. But for a person with hearing loss, speaking is often hard without proper training. Like all other communication tools, the skill of speaking must be learned. Often a speech-language pathologist (a professional trained to teach people how to use speech and language) will work with the person with hearing loss and the family.

Speech Reading

Speech Reading (or lip reading) helps a person with hearing loss understand speech. The person watches the movements of a speaker’s mouth and face, and understands what the speaker is saying. About 40% of the sounds in the English language can be seen on the lips of a speaker in good conditions, such as a well-lit room where the child can see the speaker’s face. But some words can’t be read. For example: “bop,” “mop,” and “pop,” look exactly alike when spoken. (You can see this for yourself in a mirror). A good speech reader might be able to see only 4 to 5 words in a 12-word sentence.

Children often use speech reading in combination with other tools, such as auditory training (listening), cued speech, and others. But it can’t be successful alone. Babies will naturally begin using this building block if they can see the speaker’s mouth and face. But as a child gets older, he or she will still need some training.

Sometimes, when talking with a person who is deaf or hard-of-hearing, people will exaggerate their mouth movements or talk very loudly. Exaggerated mouth movements and a loud voice can make speech reading very hard. It is important to talk in a normal way and look directly at your child’s face and make sure he or she is watching you.

VI.Risk of Bacterial Meningitis in Children with Cochlear Implants

2002 Study of the Risk of Bacterial Meningitis in Children with Cochlear Implants

Many people have received cochlear implants to help them hear and communicate. CDC and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) carried out a study in 2002 to learn more about a possible link between cochlear implants and bacterial meningitis in children with cochlear implants. This study had two purposes: (1) to find out how many children who had cochlear implants got bacterial meningitis afterwards, and (2) to find out if there are factors that might make it more likely that someone would get meningitis after getting a cochlear implant. The study found that bacterial meningitis occurred more often in children with all types of cochlear implants than in children of the same age group in the general population. It also found that children with an implant with a positioner (a piece used in some implant models) were much more likely to get bacterial meningitis than children with other types of cochlear implants. The implant with a positioner was voluntarily taken off the market by the manufacturer in July 2002.

2004 Study of the Risk of Bacterial Meningitis in Children with Cochlear Implants

After the 2002 study was completed, the FDA continued to receive reports of bacterial meningitis in children with cochlear implants. Because of these new reports, CDC and the FDA updated the 2002 study by looking at reports that were received up to 2 years after the 2002 study ended. The purpose of this updated study was to find out if children with cochlear implants continued to be more likely to get bacterial meningitis than children of the same age group in the general population even after they had their implant in place for more than 2 years. The study found that even two years after implant surgery, children with cochlear implants with a positioner were at greater risk of developing bacterial meningitis than children in the general US population.

CDC and FDA Recommendations

Recommendations from the CDC and FDA based on this study include:

- Children should be up-to-date on vaccines at least 2 weeks before having a cochlear implant if they are not already up-to-date on these vaccinations.

- Parents of children who have already received an implant should check with their child’s doctor to ensure that their child is up-to-date on all vaccinations.

- Doctors and other health care providers should review vaccination records of their patients who are cochlear implant recipients or candidates to ensure that they have received the recommended vaccinations based on the age-appropriate schedules for high risk people.

- Parents of children with cochlear implants should be watchful for possible signs and symptoms of meningitis and seek prompt attention for any bacterial infection their child might have. Any questions parents have about their child’s health should be discussed with the child’s doctor.

- Parents of children with cochlear implants should also be watchful for signs and symptoms of an ear infection, which can include ear pain, fever, and decreased appetite. Parents should seek prompt medical attention for these signs and symptoms.

- Parents should talk about the risks and benefits of cochlear implants with their child’s doctor and should discuss whether their child has certain medical conditions that might make him or her more likely to get meningitis.

VII.Data and Statistics About Hearing Loss in Children

In the United States

- Studies have shown a range of estimates for the number of children with hearing loss, some of which are summarized in the following table.

| Prevalence Rate | Source and Year | Age Range | Type/Degree of Hearing Loss | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 14.9% of children | CDC’s Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III), 1988 – 1994 [Read articleexternal icon] | 6-19 years of age | Low- or high-frequency hearing loss of at least 16-decibel hearing level in one or both ears. | National population-based, cross-sectional survey with an in-person interview and audiometric testing at 0.5 to 8 kilohertz. |

| 5 per 1,000 children | CDC’s National Health Interview Survey, 1997-2005 [Read articleexternal icon] | 3-17 years of age | N/A | Parent-reported hearing loss based on the question, “Which statement best describes the child’s hearing without a hearing aid: good, a little trouble, a lot of trouble, or deaf?” |

| 1.7 per 1,000 babies screened | CDC’s Hearing Screening and Follow-up Survey, 2019 (Data table) | Babies | N/A | Includes only babies documented as being screened for hearing loss. Does not reflect cases of hearing loss that were identified but never reported to the state or territorial Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program. |

| 1.4 per 1,000 children | CDC’s Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program (MADDSP), 1991-2010 [Read articleexternal icon] | 8 years of age | Bilateral hearing loss of 40 decibels or more | MADDSP identifies children with moderate to profound hearing loss by reviewing existing records at multiple health and education sources. |

International

- Population-based studies in Europe and North America have identified a consistent prevalence of approximately 0.1% of children having a hearing loss of more than 40 decibels (dB) through review of health or education records, or both. Other international studies using different methods or criteria (such as screenings, questionnaires, and less severe decibel thresholds) have reported higher estimates. (Data table pdf icon[PDF – 75 KB])

Newborn Hearing Screening, Diagnosis, and Intervention

Based on data collected by CDC from states and territories for year 2019:

- Over 98% of U.S. newborns were screened for hearing loss

- Almost 6,000 U.S. infants born in 2019 were identified early with a permanent hearing loss

- The prevalence of hearing loss in 2019 was 1.7 per 1,000 babies screened for hearing loss

- Some infants needing additional testing or early intervention did not receive these important follow-up services

Source: 2019 CDC EHDI Hearing Screening and Follow-up Survey

Causes, Risk Factors, and Characteristics

- Genes are responsible for hearing loss among 50% to 60% of children with hearing loss. [Read articleexternal icon]

- About 20% of babies with genetic hearing loss have a “syndrome” (for example, Down syndrome or Usher syndrome).

- Infections during pregnancy in the mother, other environmental causes, and complications after birth are responsible for hearing loss among almost 30% of babies with hearing loss. [Read articleexternal icon]

- Congenital cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection during pregnancy is a preventable risk factor for hearing loss among children. [Read summaryexternal icon]

- 14% of those exposed to CMV during pregnancy develop sensorineural hearing loss (SNHL) of some type.

- About 3% to 5% of those exposed to CMV during pregnancy develop bilateral moderate-to-profound SNHL.

- A 2005 HealthStyles survey by CDC found that only 14% of female respondents had heard of CMV. [Read summaryexternal icon]

- About one in every four children with hearing loss also is born weighing less than 2,500 grams (about 5 1/2 pounds). [Read summaryexternal icon]

- According to ongoing tracking in metro Atlanta, the most common developmental disability to co-occur with hearing loss is intellectual disability (23%), followed by cerebral palsy (10%), autism spectrum disorder (7%), and/or vision impairment (5%). [Read articleexternal icon]

Transition Into Adulthood

A CDC study that followed school-aged children identified with hearing loss into young adulthood (21 through 25 years of age) found that:

- About 40% of young adults with hearing loss identified during childhood reported experiencing at least one limitation in daily functioning. [Read summaryexternal icon]

- About 71% of young adults with hearing loss without other related conditions (such as intellectual disability, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, or vision loss) were employed. [Read summaryexternal icon]

Economic Cost

- During the 1999 – 2000 school year, the total cost in the United States for special education programs for children who were deaf or hard of hearing was $652 million, or $11,006 per child. [Read reportexternal icon]

- The lifetime educational cost (year 2007 value) of hearing loss (more than 40 dB permanent loss without other disabilities) has been estimated at $115,600 per child.1

- It is expected that the lifetime costs for all people with hearing loss who were born in 2000 will total $2.1 billion (in 2003 dollars). [Read article]

- Direct medical costs, such as doctor visits, prescription drugs, and inpatient hospital stays, will make up 6% of these costs.

- Direct nonmedical expenses, such as home modifications and special education, will make up 30% of these costs.

- Indirect costs, which include the value of lost wages when a person cannot work or is limited in the amount or type of work he or she can do, will make up 63% of the costs.Note: These estimates do not include other expenses, such as hospital outpatient visits, sign language interpreters, and family out-of-pocket expenses. The actual economic costs of hearing loss, therefore, will be even higher than what is reported here.

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Information System (EHDI-IS) Functional Standards

EHDI-IS Functional Standards Overview

This document summarizes recommendations made by the 2015 Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Information System (EHDI-IS) Functional Standard Working Group (FSWG), on the technical function requirements for a complete jurisdictional EHDI-IS. The FSWG consisted of members of the CDC EHDI team and program managers/data system experts from nine jurisdictions. These Standards were initially drafted by CDC EHDI program staff and then discussed and reviewed with the FSWG through bi-weekly conference calls. Intended users of these standards include state and territorial EHDI program managers, EHDI-IS developers/vendors, and system evaluators.

EHDI-IS Functional Standards

This document is divided into 3 main sections:

- General Considerations delineates key background realities under which the Functional Standards should be interpreted and implemented

- Programmatic Goals lays out the foundational goals that these Functional Standards are intended to address.

- Functional Standards by Programmatic Goal describes specific standards that address each of the Programmatic Goals.

Appendix-A excel icon[XLS – 22 KB]: Data item list and data definitions of categorical data items.

Appendix-B pdf icon[PDF – 195 KB]: Six dimensions of EHDI Data Quality Assessment

General Considerations

- These functional standards are intended to identify the operational, programmatic, and technical criteria that all jurisdictional EHDI programs should implement during the process of developing, using, and evaluating an EHDI Information System (EHDI-IS).

- The Functional Standards are NOT intended to provide specifications on how those functions are supposed to be implemented.

- In some cases, current state law(s) or policies may preempt full implementation of these standards. In these instances, an unmet standard may serve as a suggestion for possible future revisions.

Programmatic Goals

- Document unduplicated, individually identifiable data on the delivery of newborn hearing screening services for all infants born in the jurisdiction.

- Support tracking and documentation of the delivery of follow-up services for every infant/child who did not receive, complete or pass the newborn hearing screening.

- Document all cases of hearing loss, including congenital, late-onset, progressive, and acquired cases for infants/children <3 years old.

- Document the enrollment status, delivery and outcome of early intervention services for infants and children <3 years old with hearing loss.

- Maintain data quality (accurate, complete, timely data) of individual newborn hearing screening, follow-up screening and diagnosis, early intervention and demographic information in the EHDI-IS.

- Preserve the integrity, security, availability and privacy of all personally-identifiable health and demographic data in the EHDI-IS.

- Enable evaluation and data analysis activities.

- Support dissemination of EHDI information to authorized stakeholders.

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention and Electronic Health Records Technology

This information is for:

- Program directors of state Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs,

- Developers of EHDI computer-based information systems, and

- Vendors of electronic health records systems.

EHDI staff and technical experts can use this information to achieve interoperability and thus to improve how data is collected, analyzed, and used.

Interoperability describes the extent to which systems and devices can exchange data, and interpret that shared data. In healthcare, interoperability means the ability of health information systems to work together within and across organizational boundaries to advance effective delivery of healthcare for individuals and communities.

The CDC Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Team have been collaborating with national and international organizations on standards for improved interoperability between clinical electronic health records (EHR) and public health information systems. This joint effort is working to develop, test and adopt the new standards.

The links and downloadable documents below can be used to access content related to each output area.

Exit Notification/Disclaimer Policy

- Links with this icon (

) indicate that you are leaving a CDC Web site.

- The link may lead to a non-federal site, but it provides additional information that is consistent with the intended purpose of a federal site.

- The Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) cannot attest to the accuracy of a non-federal site.

- Linking to a non-federal site does not constitute an endorsement by HHS or any of its employees of the sponsors or the information and products presented on the site.

- You will be subject to the destination site’s privacy policy when you follow the link. For more information on exit notifications and disclaimers for non-federal Web sites, the following resources may be helpful:

There are four sections below with several Web links; each provides some of the information needed to learn about the recent improvements.

- Code Sets:

What this is: A “code set” is any set of codes used for encoding data elements, such as tables of terms, medical concepts, medical diagnosis codes, or medical procedure codes. Code sets developed for EHDI include hearing screening procedures and results, risk factors, and other medical diagnosis and intervention codes related to infant hearing loss.

- Newborn Screening Coding and Terminology Guide

- Purpose: To provide codes and terminology for newborn hearing screening procedures, results, and risk factors for infant hearing loss.

- Standard System(s): LOINCexternal icon®, SNOMED-CTexternal icon

- View/Downloadexternal icon

- Data Interchange Implementation Guides

What this is: Technical guidelines on how to implement interoperability standards to support data exchange among different health information systems, including clinical EHR, healthcare device, and public health tracking and surveillance systems.

- HL7 Version 2.6 Implementation Guide: Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Results:

- Purpose: To standardize how newborn hearing screening information is transmitted from a point of care device to an interested consumer such as public health

- Standard System(s): HL7 v2.6external icon

- View/Downloadexternal icon

- IHE Quality, Research and Public Health Technical Framework Supplement: Newborn Admission Notification Information (NANI)

- Purpose: To describe the content needed to communicate a timely newborn admission notification electronically from a birthing facility to public health. This profile is being implemented for EHDI but could be used for Immunization programs, Newborn Bloodspot Screening, Critical Congenital Heart Disease, or Communicable Disease Reporting.

- Standard System(s): HL7 v2.3external icon, v3 messagingexternal icon

- Viewexternal icon/Download (.pdfpdf iconexternal icon)

- IHE Quality Research and Public Health Technical Framework Supplement: Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI)

- Purpose: To address information exchange needed in the development of a hearing plan of care for a newborn. It specifies the content for a Hearing Plan of Care (HPoC) document. It also specifies the message constraints for a hearing screening device to report a screening interoperability also facilitated by the NANI and QME-EH profiles.

- Standard System: HL7 CDA R2external icon

- EDHI-Hearing Screening Device Messageexternal icon/Download (.pdf)pdf iconexternal icon

- IHE Quality Research and Public Health Technical Framework Supplement: Quality Measure Execution – Early hearing (QME-EH)

- Purpose: to define the patient-level quality report needed for the Hearing Screening Prior to Hospital Discharge (NQF 1354) electronic clinical quality measure (eCQM) defined by the CDC EHDI program; the measure is used to assess the quality of the process of hearing screening for newborns. (See Section 3 Below)

- Standard System: HL7 QRDAexternal icon

- Viewexternal icon/Download (.pdf)pdf iconexternal icon

- Electronic Quality Measure Specifications

What this is: Standards for electronically representing clinical quality measures, which are tools that are defined to help measure and track the quality of health care services provided by professions and hospitals within our health care system.

- Hearing Screening Before Hospital Discharge (NQF1354/NQF1354e)

- Purpose: To define electronic clinical quality measure for newborn hearing screening quality reporting, adopted by the CMS EHR “Meaningful-Use” Incentive Program for Hospitals and Critical Access Hospitals

- Standard System: HL7 HQMF (QDM based)external icon

- View/Download: NQF1354external icon

- EHR System Public Health Functional Profile

What this is: Functional requirements and criteria to support public health-clinical information collection, management and exchanges for specific public health programs (domains). The profile may serve as the reference for certification of EHR systems that include functionality to support Public Health domains.

- HL7 EHR System Public Health Functional Profile

- Purpose: To define functional requirements and criteria to support public health-clinical information collection, management and exchanges for specific public health programs (domains)

- Standard System: HL7 EHR-S Functional Modelexternal icon

- View/Downloadexternal icon

VIII.Articles and Key Findings About Hearing Loss

Key Findings

Is Your Child Who is Deaf or Hard of Hearing Ready for Kindergarten?

Study found that receiving early intervention services before 6 months of age can help children who are born deaf or hard of hearing (D/HH) get ready for kindergarten.

(Published: September 28, 2020)

Featured Articles

Newborn Hearing Screening Can Improve Reading Skills

This study looked at reading proficiency results from the Colorado Student Assessment Program among 321 children who are deaf or hard of hearing, assessed in grades 3 through 10.

(Published: September 22, 2021)

Supporting Deaf Children During COVID-19

Learn how two Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs are providing essential services to these children and their families during COVID-19.

(Published: May 29, 2020)

Can Your Baby Hear You Say “I Love You?”

Find out why hearing screening is important, how to get your baby screened, and what to do with the results.

(Published: May 29, 2019)

Vocabulary and Children with Hearing Loss

A study recently published in the journal, Pediatrics, entitled “Early Hearing Detection and Vocabulary of Children with Hearing Loss,” found that early diagnosis and intervention for children with hearing loss can help them develop communication skills.

(Published: July 10, 2017)

Scientific Articles

These CDC scientific articles are listed in order of date published, from 2006 to present.

Middle Ear Effusion in Children with Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection

The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal, 2020 4(39) 273-276

Chung W, Leung J, Lanzieri TM, Blum P, Demmler-Harrison G, et. al

[Read Summaryexternal icon]

Evaluating Data Quality of Newborn Hearing Screening

The Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, Vol. 4, Iss. 3 (2019)

Maria C. Sanchez Gomez, Kelly Dundon, Xidong Deng

[Read Summaryexternal icon]

Valganciclovir Use Among Commercially and Medicaid-insured Infants With Congenital CMV Infection in the United States, 2009–2015

Clinical Therapeutics 40(3), pp. 430-439.e1

Leung, J.,Dollard,S., Grosse,S.D., Chung, W., Do, T., Patel,Lanzieri, T.M.

[Read Articleexternal icon]

Electronic Clinical Quality Measure (eCQM) Standards Landscape: An EHDI Case Study

The IHE Quality, Research and Public Health (QRPH) Technical Committee

White paper published February 6, 2018

Contributor: Deng, X.

[Read Articlepdf iconexternal icon]

Restructuring Data Reported from State Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) Programs: A Pilot Study

Journal of Early Hearing Detection and Intervention, 3(1), 57-66.

Alam, S. O’Hollearn, T. Beavers, J. Rex, A. K. Cunningham, R. F. Chung, W. Deng, X. & Do, T. N. (2018).

[Read Articleexternal icon]

Reporting Newborn Audiologic Results to State EHDI Programs

Ear & Hearing 2017 Sep-Oct; 38(5): 638–642.

Chung, W., Beauchaine, K., Grimes, A., O’Hollearn, T., Mason, C., Ringwalt, S.

[Read Articleexternal icon]

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention-Pediatric Audiology Links to Services EHDI-PALS: Building a National Facility Database

Ear & Hearing 2017;38;e227–e231)

Chung, W., Beauchaine, Hoffman, J., Coverstone, K., Oyler, A., Mason C.

[Read Articleexternal icon]

Hearing Loss in Children With Asymptomatic Congenital Cytomegalovirus Infection

Pediatrics; March 2017, Volume 139, number 3

Lanzieri, T.M., Chung, W et al.

[Read Articleexternal icon]

Long-term outcomes of children with symptomatic congenital cytomegalovirus disease

Journal of Perinatology; April, 2017, page 1-6

Lanzieri, T.M., Leung, J., Caviness, A.C., Chung, W et al.

[Read Articleexternal icon]

Progress in Identifying Infants with Hearing Loss

MMWR; 2015; 64(13); 351-356.

Williams, T. R., Alam, S., Gaffney, M.

[Read article]

Newborn Hearing Screening Can Improve Reading Skills

New findings from a studyexternal icon funded by CDC’s Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program were recently published in the journal Pediatrics. The article, entitled “Reading proficiency trends following newborn hearing screening implementation,” describes trends in reading proficiency among school-aged children in Colorado who are deaf or hard of hearing.

Reading Proficiency of Children with Hearing Loss

This study looked at reading proficiency results from the Colorado Student Assessment Program among 321 children who are deaf or hard of hearing, assessed in grades 3 through 10. The test years (2000–2014) included children born before and after implementation of Universal Newborn Hearing Screening (UNHS) and Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) in an urban Colorado school district.

Findings showed that reading proficiency significantly improved for each group of children (by birth year and grade overall) following implementation of UNHS/EHDI. This study is the first to demonstrate long-term improvement in reading proficiency over time among children with hearing loss, as UNHS/EHDI programs were being implemented. By the end of the study, more than 80% of children in Colorado met the national EHDI 1-3-6 benchmarks.

However, researchers identified a sociodemographic disparity, with greater improvements in reading proficiency among children in more economically advantaged families. This health equity issue could be due to differences in access to services.

CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities’ goal is to give every child with hearing loss the same opportunities to succeed as their hearing peers. This study shows that following the implementation of UNHS/EHDI, children with hearing loss experienced notable improvements in reading proficiency.

It is recommended that all babies are screened for hearing loss no later than 1 month of age.

If a baby does not pass the hearing screening, it is important that he or she gets a diagnostic hearing test and evaluation by a hearing specialist as soon as possible, but no later than 3 months of age.

Intervention services are recommended for children diagnosed with hearing loss, beginning as early as possible, but no later than 6 months of age.

Types of Interventions

There are different types of communication options and interventions available for children with hearing loss. With help from healthcare providers and intervention specialists, families can select the options that best meet their needs. These are some of the possible options:

- Learning other ways to communicate, such as sign language.

- Technology to help with communication, such as hearing aids and cochlear implants.

- Family support services, such as support groups.

What Can Be Done

Families, pediatric healthcare providers, and hearing specialists all play a role in getting a child’s hearing assessed in a timely manner and can help ensure prompt enrollment in intervention when necessary.

Supporting Deaf Children During COVID-19

Thousands of babies are born deaf or hard of hearing in the United States each year. It’s important that they are identified early and receive appropriate support services in a timely manner. Learn how two Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) programs are providing essential services to these children and their families during COVID-19.

About 1 in 500 babies in the United States are born deaf or hard of hearing (DHH). When identified at birth, babies who are DHH can begin intervention early and are more likely to achieve language, cognitive and social development on par with typically developing peers.1 Every state has an Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program that works to ensure that babies who are DHH are diagnosed early and receive the services they need on time.

Amid the concerns and changes that have resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic, EHDI programs are finding creative and successful ways to use technology to provide access to the resources and services needed by the children and families they serve. These efforts are helping children to achieve their full potential in language, cognitive, and social development and keeping their families informed during this time. Here are just a few examples of how programs are adapting and succeeding.

Utah’s Sound Beginnings Program Moves Online

As a result of moving all of their educational services for children from birth to 6 years of age who are DHH to an on-line format, teachers at the Sound Beginnings program in Utahexternal icon are using tele-interventionexternal icon to help infants and children who use hearing technology to develop listening and spoken language skills. They also help parents learn strategies for working with their child to develop spoken language within their natural home environment. With the COVID-19 pandemic and parents spending more time at home, Sound Beginnings is now working with more fathers in providing day-to-day Early Intervention services – something they have tried to do for years with limited success.

Liam Nay is 6 years old and has bilateral cochlear implants. His father, Sam, has been excited about Liam’s progress in the Sound Beginnings program over the past 4 years. Because he is spending more time at home, Sam is now able to be more extensively involved in supporting his son with his on-line kindergarten class and individual language intervention sessions. Accustomed to having his mother attend the parent-child therapy sessions, Liam beamed, “You’re okay to have in class too, Dad!” Sam noted that even though he and his wife have always worked together to help with Liam’s therapy at home, “It has been a big help to Liam to get to spend time with both of us in different sessions with his teachers. When both of us get to spend time working with him, he knows that he is important to both of us.”

Visit the National Center for Hearing Assessment and Managementexternal icon (NCHAM) to learn more about telehealth and how it can be used to support clinical health care and education via 2-way video conferencing.

Hands & Voices Keeps Families Connected

Hands & Voicesexternal icon, an organization dedicated to supporting families with children who are DHH, knew they had to get creative to keep families connected during this time of social isolation. The Kentucky Hands & Voicesexternal icon came up with the idea of a “Thursday Thirties” series, where every Thursday evening, they would have an on-line event to interact with families and answer their questions. For one of the events they partnered with Virginia Moore, executive director at the Kentucky Commission on the Deaf and Hard of Hearing (KCDHH)external icon. Virginia answered a series of questions from Hands & Voices kids about her role as an American Sign Language interpreter for the governor of Kentucky during the daily COVID-19 updates. She also spoke about her partnership with Hands & Voices and the importance of communication for children who are DHH.

Visit Hands & Voicesexternal icon to learn more about the services and support they offer to families of children who are DHH.

The stories above are just a few examples of how health care providers and organizations are adapting to provide education and other services to children who are DHH and their families. To learn more, view NCHAM, and Hands and Voices webinar seriesexternal icon about bright spots and innovative activities during COVID-19 for children who are DHH.

The American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) offers this advice to families whose services have been interrupted

- Communicate with your service coordinator. Check in to see if services can continue virtually for the time being.

- Find out best way to reach your service provider. See if your provider will be available by phone/email/video conferencing to answer questions and offer suggestions, even if formal sessions aren’t taking place.

- Ask if changes to your child’s Individualized Family Service Plan (IFSP) pdf icon[460 KB/6 pages] are needed—If changes are needed, how you can work with the rest of the IFSP team to make those changes.

- Trust yourself. You know your child best. Follow your instincts on what your child needs and which aspects of daily activities and routines are most conducive to their progress.

- Remember your parent training. Consider the strategies and interactions you already know work well and what you are doing to foster communication development.

- Let real life be the guide. Young children learn best in the context of real-life activities and with the people who are most important to them. Weave communication interactions and goals into everyday routines and activities such as mealtime, bath time, changing time, playtime, and household chores.

- Engaging in early intervention services is a choice. It’s okay to say that you need to cancel services if virtual or other modified services are not a good fit for your family.

Visit ASHA’s Better Hearing and Speech Month webpageexternal icon to find additional information and resources for parents.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) supports the continuation of newborn screening services during COVID-19

- The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)external icon supports the continued provision of health care for children during the COVID-19 pandemic unless community circumstances related to the pandemic require necessary adjustments.

- The AAP recommends that pediatricians continue to follow federal and state guidelines on newborn screening, including those for newborn hearing screening and follow-up.

Additional Resources

CDC’s Hearing Loss in Children

National Center for Hearing Assessment and Management (NCHAM)external icon

American Academy of Pediatricsexternal icon

American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA)external icon

Hands & Voicesexternal icon

Sound Beginnings at Utah State Universityexternal icon

References

- Christine Yoshinaga-Itano C, Sedey A.L,Wiggin M, Chung W. Early Hearing Detection and Vocabulary of Children with Hearing Loss. Pediatrics. 2017; 140(2): e20162964; DOI: https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2016-2964external icon

Can your baby hear you say “I love you?”

The best way to find out if your baby may be deaf or hard of hearing is by a hearing screening. Early diagnosis and intervention will help them reach their full potential.

Thousands of babies are born deaf or hard of hearing each year in the United States. Babies diagnosed early with hearing loss and begin intervention early are more likely to reach their full potential. The best way to find out if your baby may be deaf or hard of hearing is by a simple hearing test, also called a hearing screening.

Why is a hearing screening important for my baby?

Learn more about outcomes associated with early hearing detection and intervention:

Reading Proficiency Trends Following Newborn Hearing Screening Implementationexternal icon

Starting from day 1, babies begin to learn language skills by listening to and interacting with those around them. If babies miss these opportunities, their language development can be delayed. Many times, children’s hearing loss is not obvious and can go unnoticed for months or even years.

Hearing screening at birth can determine if your baby may have a hearing loss and if more tests are needed. An early diagnosis is essential to help babies who are deaf or hard of hearing reach their full potential, and allows families to make decisions about the intervention services that are best for their baby’s needs. Early diagnosis of hearing loss and beginning intervention helps to keep children’s development on track and improve their future language and social development.

Your baby probably had a hearing screening

Almost all states, communities, and hospitals now screen newborns for hearing loss before the babies leave the hospital. The hearing screening is easy and painless, and it can determine if more testing is needed. In fact, many babies sleep through the hearing screening, and the test usually takes just a few minutes.

What if my baby did not pass the hearing screening?

Additional testing is the next step to tell if your baby has hearing loss and what type of loss it is. A healthcare professional trained to test hearing, such as an audiologist, will be able to perform more detailed hearing tests. Your baby’s doctor (or an ear, nose, and throat doctor) should perform or order any medical tests needed to find out the cause of the hearing loss.

Making sure your baby gets this additional testing quickly is also important. CDC-funded research shows just how important it is. Children with hearing loss who are identified before 3 months of age, and receive services before 6 months of age, have better vocabularies than those identified or receiving services later. For more information about this research, visit Giving Every Child the Gift of Words

If my baby passed the hearing screening, is everything fine?

Because a newborn baby can pass the hearing screening and still develop a hearing loss later, your baby’s doctor should routinely follow your baby’s general health and development.

For more information, visit CDC’s Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) website.

View large image and text description

View large image and text description

Where can I go for help?

Every state has a program that works to help make sure that babies who are deaf or hard of hearing are diagnosed early. If you have any concerns about your baby’s hearing, ask the doctor for a hearing test or screening as soon as possible. To learn more about this topic, you can also call toll free 1-800-CDC-INFO or visit the CDC EHDI Program site.

The Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) program works with your state to ensure that all babies are screened for hearing loss and receive any needed follow-up tests and services. CDC’s EHDI program supports the ongoing search for new ways to improve services. To learn more about CDC’s important role in helping children who are deaf and hard of hearing, download a fact sheet pdf icon[439 KB, 2 Pages, 508] and watch a video in American Sign Languagemedia icon.

Giving Every Child the Gift of Words

While hearing loss can affect a child’s ability to develop language and words, a study funded by CDC’s Early Hearing Detection and Intervention Program recently published its results in the journal Pediatrics. The article, entitled “Early Hearing Detection and Vocabulary of Children with Hearing Loss,” described the finding that early diagnosis and intervention for children with hearing loss can help them develop these communication skills.

Vocabulary of Children with Hearing Loss

The study looked at 448 children with hearing loss between 8 and 39 months of age across 12 states, and compared their vocabulary (spoken or using sign language) to the typical vocabulary of a child of the same age. Children with hearing loss who met all three guidelines in the recommended time had much better vocabularies than those who were not identified or did not receive treatment within the 3 and 6 month guidelines, respectively.

Screening newborns for hearing loss within the one month guideline is very successful. In fact, in 2014, 96% of U.S. children were screened for hearing loss no later than 1 month of age1. However, in this Pediatrics study, just over 40% of participating children did not meet the important next steps of having their hearing loss diagnosed by 3 months and beginning intervention by 6 months.

CDC’s National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities’ goal is to give every child with hearing loss the same opportunities to succeed as their hearing peers. The recent study shows that children with hearing loss who get hearing screening, diagnosis, and intervention services according to the EHDI 1-3-6 guidelines can have much better vocabulary development.

It is recommended that all babies are screened for hearing loss no later than 1 month of age.

If a baby does not pass the hearing screening, it is important that he or she gets a diagnostic hearing test and evaluation by a hearing specialist as soon as possible, but no later than 3 months of age.

Intervention services are recommended for children diagnosed with hearing loss, beginning as early as possible, but no later than 6 months of age.

Types of Interventions

There are different types of communication options and interventions available for children with hearing loss. With help from healthcare providers and intervention specialists, families are able to select the options that best meet their needs. These are some of the possible options:

• Learning other ways to communicate, such as sign language.

• Technology to help with communication, such as hearing aids and cochlear implants.

• Medicine and surgery to correct some types of hearing loss.

• Family support services, such as support groups.

What Can Be Done

More research is necessary to understand how children with hearing loss can continue to improve their vocabulary development as they grow older. Families, pediatric healthcare providers, and hearing specialists all play a role in getting a child’s hearing assessed in a timely manner and achieving prompt enrollment in intervention, if necessary.

For more information about CDC’s resources, please visit

• The Pediatrics Studyexternal icon

• Facts about Hearing Loss

• Hearing Loss in Children Homepage

• A Parent’s Guide to Hearing Loss

• Educational Materials

• Podcast in English [PODCAST – 10:46 minutes] or in Spanish [PODCAST – 13:11] on Early Hearing Detection and Intervention

IX.Research and Tracking of Hearing Loss in Children

Determining How Many Children Have Hearing Loss

By studying the number of children diagnosed with hearing loss over time, we can find out if the number is rising, dropping, or staying the same. We can compare the number of children with hearing loss in different groups of people. This information can help us look for causes of hearing loss and help communities plan for services.

We do not know exactly how many children have hearing loss. CDC data have shown that approximately 1 to 3 per 1,000 children have hearing loss. Other studies have shown rates from 2 to 5 per 1,000 children.

Data chart of prevalence studies

Following are activities that CDC conducts or funds in order to learn more about the number of children with hearing loss:

Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program (MADDSP)

CDC tracks the number of eight-year-old children in a five-county area in metropolitan Atlanta, Georgia who have moderate to profound hearing loss in both ears. For this project, we define moderate to profound hearing loss as a 40 dB or greater loss in the better ear, without the use of hearing aids.

The average annual prevalence

of moderate to profound hearing loss from 1991 through 2010 was 1.4 per 1,000 or 1 in 714 children in metropolitan Atlanta.

National Surveys